a couple of weeks ago i read about global voices book challenge on bint battuta’s blog. global voices along with unesco asked people to read their way around the world for unesco world book day which is today:

The Global Voices Book Challenge is as follows:

1) Read a book during the next month from a country whose literature you have never read anything of before.

2) Write a blog post about it during the week of April 23.

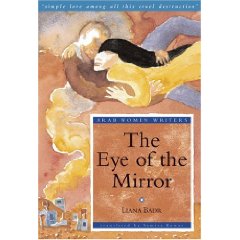

bint battuta seems to already have her book review up on her blog. she read mohamed makhzangi’s memories of a meltdown. she fudged the rules a bit and i am going to a lot. the rules say you must read a book from a country whose literature you have never read anything of before. but given the paucity of international literature in bookshops or in libraries in palestine i read a novel by palestinian novelist liana badr entitled the eye of the mirror or عين الوراة. i had started reading it a few months ago but got side-tracked with work so this was a great excuse to get back to it. the novel is set in tel al-za’atar refugee camp in lebanon from 1975-76 when it was besieged by lebanese kata’eb militias. liana badr, who is a journalist as well as a novelist, was in lebanon at the time and later spent seven years documenting the massacre in the camp. the novel was first published in arabic in morocco in 1991, although badr told me a few months ago that she wanted to publish it with al adab in lebanon and they told her that the censors would not approve its publication. i have read badr’s other translated novel, Balcony Over the Fakahani or شرفه على الفكهاني which is also quite moving and also set in lebanon during the civil war.

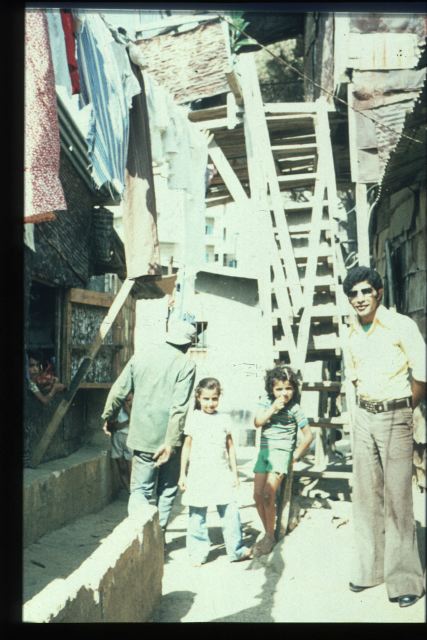

but this novel is different and really important for literary and historical reasons. while there is much written about the israeli-kata’eb massacre of shatila refugee camp and the surrounding sabra neighborhood, there is little to nothing written about the massacre of over 4,000 palestinians in tel al-za’atar refugee camp. unlike shatila, which still exists today, tel al-za’atar was destroyed and the 12,000 palestinian survivors fled to other refugee camps, many of them to nahr el bared refugee camp in northern lebanon until the lebanese army destroyed that camp in 2007. for those interested in the subject from an historical perspective i highly recommend anything by rosemary sayigh. and those who want to see some rare images from the camp you can check out benno karkabé’s photographs of which the image above is one. but the novel does an amazing job of chronicling the events in a lyrical way. jordanian novelist fadia faqir, one of my favorite writers, authored the introduction to the novel, and samira kawar translated it.

the novel focuses on a variety of characters, but most of the central characters are women. and she grounds the story from the first page in an oral tradition from scheherazade’s tales told to her husband in a thousand and one nights which she used to save her community from his wrath. thus the narrator opens the novel with a direct address to the readers telling us:

You are insistent, calling again. You want me to tell you the story of Scheherazade, who rocks the sad king on her knees as she sings him tales from wonderland. Yet you know that I am not Scheherazade, and that one of the world’s greatest wonders is that I am unable to enter my country or pass through the regions around it. Do not be surprised. Let us count them country by country. (1)

rendering strange the reality of palestinians inability to travel to–let alone return to!–their land gives the opening narration a bit of a fantastical feel, until she grounds the narrative in historical reality:

I begin with the tale of a girl or a woman. I tell perhaps of you and I, or of women and men whom I have never met. I tell of an alley, a street, a neighborhood or a city. Or perhaps of a camp, of a camp, of a Tal! Tal Ezza’tar for example…Now you shake your head reproachfully again, fearful that the story will turn into political rhetoric like the slogans we’ve become weary of. Your eyelids bat mockingly inmy face, hinting it is necessary to reassure you that what you fear will not happen. But I am compelled to begin with Ezza’tar, Tal Ezza’tar in particular, not only because of its poetic name, but for many reasons which I am under no obligation to reveal now. (2)

like scheherazade badr’s narrator makes it clear that she will tease us with the plot as a way to keep us as her interlocutors. she delays our understanding of characters, setting, and events letting them unravel as scheherazade famously did in a thousand and one nights. in the arabic version of the novel badr used palestinian dialect so the spellings of transliterated words in her novel reflect this accent (hence her spelling of the camp’s name). the novel opens with the protagonist, aisha, who is actually my least favorite character in the novel, who at the time is working as a maid at a lebanese christian boarding school outside the camp. she is called home from work by her parents because of the april 1975 massacre of palestinians on a bus in ain al roumaneh, but the we hear about the incident on the bus several times before we learn the context of it. the narrator tells us:

The bus. Perhaps if that massacre hadn’t happened, they would not have taken her out of school. Her mother used to say, “The bus,” wincing as though she were being struck on the forehead by a ray of very strong sunlight. She would lick her oval-shaped lips with her cracked tongue, panting as she moved the fingers of her right hand over her chest as though she were shaking imaginary dust from her wide dress.

“The bus. Woe is me. What a catastrophe! What a shame! What had the young men and the boys done to get killed in this way? Twenty of them, my dear. Twenty. That’s what your father said. They attacked them, bang, bang.” (8).

we don’t learn who was on the bus or what it means for aisha until later in the novel. the novel delays our understanding as readers, but also aisha’s as her character is a rather naive young woman who is relatively sheltered as compared to hana, a character i like much more. badr also delays our knowledge of the family’s flight from yaffa, their village of origin in palestine, through fairy tale narrative techniques such as the repetition of “once upon a time” as well as aisha’s fantasies about her prince charming, george haddad a nom de guerre for ahmed al-ashi, a member of the resistance with the democratic front for the liberation of palestine (dflp). george is originally from tulkarem, but he left to fight with the resistance in jordan and was expelled to lebanon in 1970 after black september with the rest of the freedom fighters. his friendship with aisha’s parents and the conversation he has with her family is often as a kind of teacher about life in palestine in ways that disrupt stereotypes about religious differences or the divide between rural and urban palestinians as a way to assert unity among palestinians as when he tutors aisha’s younger sister ibtisam:

Speaking to him again, she said: “Why d’you pronounce the ‘ka’ as a ‘cha’ when you speak? Aren’t you worried that your fiance’s family will think you’re a peasant?”

“I am a peasant.”

She jumped with joy at the strange news, which aroused her interest: “A real live peasant? does that mean that you plant and harvest the land?”

“I’m a peasant and the son of peasants. But I’ve no longer got any land to plant and harvest.”

“So how d’you make a living?”

“We’re just like everybody else. My brothers and sisters and I, each of us is homeless in a different country.” (58)

conversations such as this one, various characters remembering life in palestine, plot details about aisha’s deisre to marry george, and later her marriage to feda’ee hassan, and depictions of daily life in the camp cover the first half of the novel. the gap between the ain al roumaneh bus massacre and the eruption of a full-scale attack on tel al-za’atar camp, mimicking the lull in the characters’ daily lives as they try to carry on in between clashes. after aisha’s marriage to hassan his mother, um hassan, shares her family’s story one morning with her new daughter-in-law that encapsulates many of the family’s stories in the novel:

With an automatic strength, she held back her words, which had turned into something resembling the stone that one rubs before prayer, hoping to pierce it and squeeze out whatever water might be inside it when none is available for ablutions. But her overwhelming sadness broke through her silence, and she spoke once more: “Eh…We came out of Palestine. We were in the orchards picking olives when Assafsaaf, which was the nearest village to us, fell. The Haganah gangs slaughtered a lot of people, and also raped many women. My neighbor’s niece was slaughtered in front of her father. We had no arms. We thought it would be a good idea to leave for a short time so that what happened to the people of Assafsaaf and Ain Ezzeitoun, which King Abdullah had surrendered, and Deir Yassin would not happen to us. We went north. We didn’t see anything, and never looked back, because we were so sure that we would return a few days later. In Bint Jbeil, we found that the UN were putting people into cars and taking them to Burj Esh-Shemali. People were surviving on almost nothing. When it snowed on us in Burj Esh-Shmeali, they moved us to Nahr El-Barid in Tripoli.” (109)

um hassan’s story here serves both as historical memory–of slaughter and flight–and also as premonition for what will come to tel al-za’atar camp in the coming weeks and months. just as the narration shifts from one character to another so as to give a variety of perspectives from palestinian refugees’ experiences, so too does the narrator shift at times to a voice that inserts the author herself entering the narrative:

That was a sight I shall never forget. The day I managed to enter the camp of Tal Ezza’tar, being one of the few people who managed to reach it between two sieges, I saw the apples scattered around on the streets, their skins shrunken and wrinkled. But they had kept their pretty red colour. I had said to myself: “Ezza’tar? Why don’t they call it Attuffah?” At that moment my grandfather’s home in Wadi Attufah, the valley of apples, in Hebron flashed into my mind’s eye. And I remembered my mother, Hayat, in the mid-fifties. She had lived at my grandfather’s house temporarily before moving into the attic above the school, which was afflicted with measles and frost-bite. How innocent I had been. I went to my grandfather simply to tell him how I had heard my mother complaining to Hajjeh Salimah about the hassle and pain of living with my grandfather’s fourth wife. I had told him. I was three years old. My mother and Hajjeh Salimah had later accused me of blowing the whistle on her and reporting her grievances to the tribe elder, who wore a red tarboush with a silk tassle. But, what I want to say is this. Every place I saw later would always remind me of my birth place in Palestine. And in Tal Ezza’tar, I recalled Wadi Attuffah in the West Bank of Palestine. My amazement increased at the dry fruit littering the place like freckles on a face that has seen too much sun. Everybody was sitting in the sun, both old and young. They had all come out of the shelters, corridors and passages to get a touch of the amber rays. Old women with patterned tattoos on their faces, which had been acquired long before their arrival in this place. They sat with their grandchildren in their laps, while the women were busy airing the sheets and blankets in which the young ones had slept during the confinement. No one looked at the scattered fruits which covered the ground like stones forgotten since the beginning of creation. The car turned and went up into the Tal. At the clinic, I was able to meet Um Jalal and the doctor who worked there. When I told them that I had come to do a newspaper report on the steadfastness of the camp on the anniversary of the emergence of the resistance, people called one another from here and there and they spoke to me. (125-126)

insertions of passages like the one above in which we imagine badr as a character in the novel taking eyewitness accounts of the people of the camp adds historical weight to the narrative. and it is through her presence that we finally learn more about characters like hana who is one of the resistance fighters badr-as-character interviews:

Like a passing arrow, Hana, entered the clinic. They introduced her to me: “Hana, the bravest wireless operator in the entire camp. No one is quite like her. She does the night shift in the wireless room, and goes with the girls to her military positions.”

I looked at her. Her eyes were green, her hair was tied back in a pony tail. She had a feminine air despite the seriousness which her difficult assignments imparted to her. I asked her: “It’s unusual for a girl to be on duty at night all by herself!”

“I’m not afraid of the night. Sometimes I used to be on duty at night, and I was not scared. The young men would be tied up along the combat lines and I would keep operating the wireless. At first, my parents wouldn’t agree to my work because they were worried about me. But I’ve done a three-month militia training course. I did it when the revolution entered the camp, and training began. They offered a course for girls. I was fourteen years old. It was a very strenuous course and I was in the third preparatory class at school.” (131)

once the intensity of the war increases, so too does the pace of the novel and the plot begins to mirror that intensity. the daily life of the women in the novel shifts to fighting to survive under siege, to collectivity:

The basement house! Voices echoing in a deep lair. The wailing of confined children and their running noses. The kerosene cookers emitting soot as they burned, and the smell of kerosene with the orange-blue flame. The arms of women moving the stone mill to crush lentils for use as a flour substitute. Discovering this new camp! It did not occur to anyone outside this besieged patch how thousands of people were living without basic necessities. No rice. No sugar. No wheat or flour. But there were lentils that were crushed and ground, and mixed with water, then fried on kerosene cookers or tin baking plates under which scraps of wood and paper were set alight. When there was no milk, they used lentil water as a substitute to feed their babies, and they used lentil yeast to make bread. Lentils became a mercy from God, quieting cries of hunger. Those who were unable to replace torn sandbags near their fortifications took cover behind lentil sacks. They hid behind them waiting for God to ease their plight. Had it not been for the blessed presence of the lentil packaging factory inside Tal Ezza’tar, hundreds would have starved long ago. (155-156)

we also begin to get more detailed narration about the freedom fighters defending the camp at this point, such as farid, whose presence in the novel is far too minimal. just as the story of the women above making do with their ingenuity and rations can be imagined in the context of so many other situations in which palestinians have been besieged–most recently, of course, in gaza–so too with farid’s story can we understand the plight of palestinians without a homeland, without an identity card, though, coincidentally he hails from gaza. when aisha’s mother, um jalal, complains about the fact that he smokes so much her son-in-law hassan tells her:

His family are all in Gaza. He’s not married and hasn’t got children, and you feel that a couple of cigarettes are wasted on him. Let him smoke as much as he likes. Why not?”

Um Jalal walked away, large masses of fat protruding from her back beneath her shapeless dress. Hassan recalled Farid with special sympathy. The homeless one! Unable to enter any country because he had no passport. Living in airports and traveling in planes. He had once tried to travel to an Arab capital to see his mother, who had come across the bridge, but he was unable to. The old lady had waited as airports took delivery of the young man, then threw him off to airports father away. His Palestinian travel document got him to Scandinavian countries after passing through African and Asian ones. Farid would enter a country and immediately became an inmate in an airport lounge until the authorities rejected him, putting him on the first departing flight. Farid had told them a lot about other Palestinian families living in transit lounges. He would guffaw as he told of how they would hang their underwear in the public bathroom. Sometimes, he would become tearful as he recalled the humiliation he had faced with security men and policemen. In the end, his case had turned into something akin to a play from the theatre of the absurd which no one would take seriously because it was merely entertainment. Finally one of the PLO offices was able to solve his problem through intensive lobbying of important people in the host country, and it was decided that he would be deported to Lebanon. Thereafter, Farid completely turned back on his plans to see his mother, and on his good intentions, which had only brought him harm. He never, ever thought of trying again, and his brothers had informed him of this mother’s death a year ago.

Although Farid had been accused of belonging to a terrorist organization, the name of which struck fear in the hearts of officials in European airports, Hassan believed that he had never even harmed an ant in his life. Duty was duty. And it was duty in any situation. it was enough that Farid had almost become the victim of his own organization when clashes had broken out in the early seventies over the concept of a Palestinian state on part of the homeland. The organization had not accepted the idea, and considered it a transgression of the sacred charter which called for the liberation of all Palestine. We cannot give up our land to the enemy, they had said. The whole of the levant will revolt one day, and we wil liberate Palestine to the last inch. The result was all too clear now. The Arab governments wanted to liberate their countries first, had been the comment of Farid. His incessant smoking provoked the anger and coughing of the middle-aged women dying for a Marlboro cigarette or any real tobacco wrapped in white paper.

The hateful church was nothing more than a wall to the fighters of the camp. They would remove it and excuse the enemy position which was crushing the people with their sniper bullets and shells. Hassan failed to understand why religion had turned into a sword against human beings. Until that moment, he could not understand how they would be able to blow up the church despite the teachings of the Quran chanted by his father, which instructed him to respect other religions. Hassan had never in his life tried to pick up a Quran and read its verses. He had become used to respecting it from afar. He had treated religion as though it were meant for old people and sheikhs who went on pilgrimage to Mecca. It was not for him, or those who were his age. The continued problems of day-to-day living had prompted families to give top priority to the education of their sons. His family had always said that the Palestinians could not win the struggle to survive without education. No home, no country and no friends. How could Palestinians struggle to survive without that weapon? It would gain them the protection they needed, and they would rebuild their shattered lives until they could return to their countries. Religion. He could not remember that anyone in his family had ever prayed, except for his elderly father. His mother had considered that working to solve the problems of being homeless refugees was a form of worship. Preserving the life that God has created is the most noble form of worship, she had always told them. So Hassan asked himself why the enemies were waging their war in the name of religion. was it because they had a lot of money, houses and factories that spared them from being overwhelmed by the problems of daily survival? but they were not all that way. Their poor were at the front, and those waging the war appeared on the social pages of the newspapers at their boisterous parties. (161-162)

i quote this long passage above because it says so much about the continuing struggle of palestinians. it speaks to so much historically and currently. farid is a resistance fighter who comes to rescue people of the camp by trying to bomb the church where most of the heavy shelling besieging the camp originates from. there are other moments like this where the context of the palestinian resistance struggle is contextualized such as hassan’s thoughts about why he fights in the resistance:

When he had grown up and gone to university, he had discovered that therw ere two civilizations living alongside one another in modern times. One was the civilization of repression, which used the most developed tools of technology to repress people and evict them from their homes, as in South Africa and Palestine. The other was the civilization of the oppressed, who could possibly win, but only possible…but if one was in one’s home and country. But here? Among strangers. How could one go on amongst those who only cared about importing cars and arcade games and the latest brands of washing powder appearing on television screens? (172-173)

while hana is the only female resistance fighter in the novel, all of the women resist in various ways. hassan’s sister amneh works in the hospital caring for patients without any medications, power, or water to treat them properly, much like gaza. she was responsible for holding patients down while their wounds were stitched without anesthesia. most of the mothers and elderly found a basement where they hid out together trying to escape the shelling, however, including her family. the narrator describes, in detail, what happens when she discovers the building had been shelled to the ground:

As she walked through a corridor of brown cloudy smoke Amneh saw herself as a sleeper sees her soul. She saw her body passing through fields of stones, crushed rocks, and pieces of debris flying about in the air. Amneh saw herself as if in a dream, as though she were crossing a desert too hot for any human to bear. Sweat flows profusely from her, dripping down her forehead, her shoulders, and beneath her arms. Powdered gypsum, or something like the white plaster used to decorate the walls of houses, stick to her hair. The clouds grew thicker, then lifted to reveal what Amneh finally realized–the shelter. Collapsed. Crumbled. Shelled. It was definitely no longer in its place. no longer remained standing. Something the mind could not grasp. But the crowds of traumatized people. They came in shocked waves. The sound of their wailing mingling with the hoarse moans coming out of the shelter convinced her, forced her to see what was happening. She went over to a man carrying a spade. He tossed it away, and threw himself on the debris to dig wit his hands. All she could get out of him was that the shells which had set the plastics on fire at the Boutajy factory had cracked the walls of the adjacent building, whose basement had housed the shelter. The enemy had shelled the five-story building continually for several days, concentrating their fire ot he exposed columns which supported it, until they had cracked and collapsed. the roof had fallen in on everyone beneath it, blocking the exit. No. everything had collapsed over them, and there was no longer any door or exit. The man was crying, shouting, screaming. His howling was lost amidst the successive waves of wailing voices coming from beneath the battered ground and from above it. People ran around here and there carrying hoes, but the were not of much use in removing the rubble of five floors, which had collapsed over the shelter, whose door had completely disappeared. At that moment, many different emotions surged through Amneh’s bosom.[…] She continued digging with the families of those who had been buried, from two o’clock in the afternoon until three o’clock the next morning. During that interval, and until it became possible to enter the shelter, Amneh did not try to look at the bodies which other rescuers pulled out. She did not want dead people. Simply, she only wanted those able to live, because she had come to hate the kind of life that was saturated with death day and night.[…] A terror that she would never experience in her life paralysed her. A terror that would crush her and would reshape and polish the hardness of her heart, making it even tougher than before. Inside the shelter, Amneh saw about four hundred bodies so disfigured that it was impossible to recognize them. They were all unimaginably mangled. A very small number of people had survived, but they too had sustained severe injuries to their limbs. Most of the mutilation had affected the heads. One woman’s intestines had spilt out, and she had died only a short time before. (191-192)

as the fighting over the course of months dies down slightly, hana learns from her work covering the wireless machine that an evacuation of the camp has been arranged. palestinian survivors of the massacre thus far, who are injured, who have been lacking food, water, and medicine for months begin the trek out of the camp on foot. many are barefoot. many, like aisha’s father assayed, find a trauma repeated as he imagines he is fleeing palestine in 1948 not tel al-za’atar in 1976. like many of the scenes in the second half of the novel, it is detailed and horrifying:

The terror. And the bodies. And Amneh, whom Um Hassan had sent ahead to find out what was happening at the to pof the road. Some of the neighbours had already left. But Um Hassan and Um Mazen were delaying their departure, hoping for a miracle that would avert the horror of falling into the hands of the besiegers. As the decision to surrender had spread through the shelters, crowds ahd surged wither towards the mountains surrounding the camp, or towards Dekwaneh that terrible compulsory route. The amputated hands and feet scattered along the Dekwaneh road, their veins being sucked by blue flies, were the true testament of the fate awaiting those who chose to head in that direction. The fighters prepard to leave by the rough mountain paths up to a small village called Mansourieh, hoping to break through enemy lines there, and then to continue on to the Nationalist-controlled area. Most of the young men and women joined those going up into the mountains, protected by an instinctive certainty that risking the unknown was better than following the voices offering people safe conduct which had suddenly blared out through several megaphones from the direction of Dekwaneh.

Amneh, with the newly-acquired military experience she had gained from her water-gathering trips, noticed that the faces of the bodies lying along the road were turned towards the camp, and she concluded that they had been shot in the back. The sounds of clashes on the road to the mountains made her aware of the new battle around the camp. (219-220)

amneh’s depiction of what she sees on the road out of the camp is a harbinger of what is to come once families choose to flee. the narrator describes the escalated horror that awaits the palestinian refugees, being made refugees yet again, upon their exit:

From then on, Khazneh saw nothing but blood. She passed the towering church which all the battles had not succeeded in destroying. She marvelled at the changed appearance of the building. It was neither destroyed, nor completely intact. Fallen, pile dup stones, and high thick walls and people standing outside them in lines. Was her eyesight playing tricks on her when she saw the building moving towards her, crawling like a giant ship that had suddenly set sail from a mythical port. Medieval flags fly over it, and knights parade on its roof upon pure-blooded saddled horses, wearing cloths flowing down their flanks. They carry quivers filled with poison-tipped arrows, and helmets and shields and pommels and whips and shining iron swords. As for the church, it continues to crawl and stretch forward with a slow deliberate movement, while they take no notice. Khazneh rubbed her eyes so that she could verify the movement towards her of the building-ship that she was seeing. She looked more carefully and saw rows of young men lined up in front of the wall of the church. Now they were hitting them on their backs with hammers, the stone pestles used in stone mortars to grind wheat and mix it with raw meat for kubbeh dough. But the hammers! They were hitting them with those hammers which had been specially made to pound red meat for that traditional dish. They ordered the prisoners to kneel and poured petrol over them. It caught fire in a split second, and some of the prisoners fainted. They sprayed bullets on those who were kneeling, after placing iron bars in the fire and using them to burn crosses onto the bellies of those who remained standing. the smell of charred flesh filled the air. Burning flesh. They began tying up the prisoners with ropes to parade them on thee astern side of the city in trucks specially brought over for that purpose. (231-212)

there are so many other scenes of horror that each one of the characters experiences and/or witnesses. indeed, each character in the novel is an eyewitness to massacre or a victim of it, in which case we, the readers, become the witness to the crime. palestinians get rounded up and put in detention centers and families are separated from each other as various members of families are murdered. aisha, the protagonist through much of the novel, and who we begin the novel with, finds herself pregnant mid-way through the narrative. she discovers this just before her husband, hassan, is murdered by kata’eb militia men. aisha manages to survive, though we do not learn the fate of all the characters by the novel’s conclusion. but her survival, like everyone’s survival in the camp, is one that just barely manages to escape fate. that she managed to live through this siege without proper food and water and under an extreme amount of trauma provides some hope in the novel’s conclusion. that there will be a new generation of palestinian babies and that this battle for palestinians to return is not over is wrapped up in aisha’s “emaciated abdomen” (264).

there is so much more to say, to share, but i hope that people will read badr’s novel on their own. and for those who want some further information on the context of tel al-za’atar refugee camp below are two articles on the larger issue of the origin of the lebanese civil war, the attacks on palestinians in lebanon, and the zionist role in collaborating with the kata’eb against the palestinians.

to everyone out there you have to know that the massacre resulted in severe criticism of Syria throughout the Arab world, and also internationally. It is also said to have contributed to the mounting Sunni Muslim dissent within the Alawi-ruled country. As a result, Syria broke off its offensive on the PLO and the LNM, and agreed to an Arab League summit which temporarily ended the Civil War.

thx for this great article my friend

Wow, thank you for your indepth review and the outstanding passages. I can tell this is a very important and moving novel and one of these days I will try to make time to read it. I am participating in the challenge as well, but I think I misunderstood what I was supposed to do. I thought we were supposed to read “about” another country…I hadn’t realized it had to be the “literature” of another country! *sigh* Oh well…next time.

Arab Muslims always fought among themselves and others and always murdered the “infedels” http://www.nrg.co.il/online/1/ART1/483/521.html What’s new? .

neither does ignorant zionist propaganda get old. they–and you–just keep repeating the same lies over and over again so as to pretend as if there is some inherent belligerence coming from arabs and muslims.

however the truth is quite different: the fighting that exists here today is due entirely to european colonialism from zionists, british, and french alike. and to read my post in any other context is to either be just plain stupid, illiterate, or to be painfully afraid of the reality and truth of the situation–whether in badr’s novel or in real life.

I have read all of the above with great interest. I made those pictures mentioned, in the summer of 1975; when a group of dutch volunteers of the Dutch Palestine Committee stayed in the school building, in Tel El Zaatar.

We worked on the road to that school; as, in winter time, the holes in the battered pavement would become pits filled with water, potential sources of diseases like dysenteria. The children would have to cross the flooded road and be subject to the disease-carrying water..

The man with the sunglasses, in the picture shown here, I forgot his name. I migth have his name in the small diary that I kept. He gave me a tour through the camp. He was the head of security in the camp. Every morning, with our morning appeal, he would demonstrate us the exercises as part of commando training. And then, as a follow-up, we ourselves would go through his ‘fitness’ program..

He was remarkably fit; one of his legs had been hit in commando action, and as a consequence he limped a bit and was unfit for field duty. It would not stop him to do the commando exercises.

I have many memories, such good memories. I was very fond of Khaled and Ben Bella. They were in their mid teens. We all had nick names, for security reasons. They were the sons of the mayor of Tel El Zaatar, I think I was also introduced to one of his daughters, or maybe she was the only one? her name was Zenab.

Ben Bella was a real fun kid. Once, I recall, we walked from the school building into the camp, and he was carrying a large container, or bottle that is, for cooking gas – butane, like people use in trailers. He struggled a bit with the item. I said, that looks heavy, will I help you out? He said, oh no, you re a guest, only if I really cant hold on anymore I will ask you, OK? That was OK with me. Then he started to breathe a bit heavier before we arrived at a shop. ” Are you sure?” “OK, if you want to take over on the way back…” Only to laugh his head off when I carried the bottle all the way back home.. after the refill..I never realised he brought in an empty one to pick up a full bottle!

The next year my girl friend, whom I actually had met in the camp the year before, and me were listening every day to a bulky transistor radio we carried around in the isle of Krete. While we had our summer holiday, our friends were besieged in Tel El Zaatar. We felt terrible. Devastated, as we knew what the Kataeb would do to our friends. And we knew there would be no help to them.

Later on we learned that ‘the doctor’ had be one of the few male survivors. He indeed was a doctor, a young man in his early 30s and always dressed in white. He spoke german and english, he had been educated in germany. We learned through his contact with one of the dutch girls that had worked in the camp that all the men we knew had been killed. Since then, there will always be moments that I have to think of Khaled and Ben Bella. And who knows what happened to Zenab.. Fatima…

I will look up my diary, and see if it contains anything of interest.

I know there was another guy in the dutch group of volunteers that took pictures, he carried his camera even where he was not allowed to do it. I have no idea why he did not come to the fore to have them published. His name was Kees. I might trace him down though he was a bit of a loner, in the group.

I had no idea about this massacre, will study it now, we know Sabra and Shatila very well, but this! Am so horrified, but why the Palestinians each time, they did nothing to anybody yet were surrounded by evildoers, the zionists being the worst