today is world refugee day. there are 42 million refugees world-wide. there are also 7.6 million palestinian refugees, who are not included in the numbers that the united nations high commission for refugees (unhcr) uses because palestinian refugees fall under the united nations relief and works agency (unrwa) which means something different in terms of protection as well as repatriation. legal scholar susan akram explains the basic legal context that define all refugees under international law and explains the different principles guiding palestinians from other refugees:

A number of international instruments affect the status of Palestinians as refugees and as stateless persons: the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention) and its 1967 Protocol (Refugee Protocol); the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons; and the 1961 Convention on the Elimination or Reduction of Statelessness. There are also three international organizations whose activities affect the international legal rights of Palestinian refugees: the United Nations Conciliation Commission on Palestine (UNCCP); the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Because of the unique circumstances of the original and continued expulsion of Palestinians from their homes and lands, Palestinians in the diaspora may be stateless persons, refugees or both. (The legal definitions of these terms, as well as the manner in which they are applied to Palestinians, will be discussed below.) As such they should be entitled to the internationally guaranteed rights offered other stateless persons or refugees in the world.

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees is the most important treaty affecting Palestinian human rights in most of the areas of the world where they find themselves. It is also the primary international instrument governing the rights of refugees and the obligations of states towards them. This Convention, and its 1967 Protocol, incorporate the most widely accepted and applied definition of a refugee, and establish minimum guarantees of protection towards such refugees by state parties. The Refugee Convention and Protocol incorporate two essential state obligations: the application of the now universally accepted definition of “refugee” which appears in Article 1A(2) of the Convention, and the obligatory norm of non-refoulement, which appears in Article 33.1 of the Convention. The principle of non-refoulement requires that a state not return a refugee to a place where his/her life or freedom would be threatened. It is important to note that nowhere in the Refugee Convention or Protocol, nor in any other international human rights instrument, is there an obligation on any state to gratn the status of political asylum or any more permanent status than non-refoulement.

The simple recognition that an individual meets the criteria of a “refugee” as defined in the Convention, however, triggers significant state obligations towards them, not the least of which is the obligation of non-refoulement. The Convention requires states to grant refugees a number of rights which Palestinians are often denied, including: identity papers (Article 27); travel documents (Article 28); freedom from unnecessary restrictions on movement (Article 26); freedom from restrictions on employment (Articles 17 and 18); basic housing (Article 21); welfare (Article 23); education (Article 22); labour and social security rights (Article 24); and freedom of religion (Article 4). It also makes them eligible for more permanent forms of relief such as residence and citizenship, subject to the discretion of the granting state.

The Convention and Protocol define a “refugee” as:

[a person who], owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence is a result of such events, is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

This author contends that the Convention Article 1A(2) definition was never intended to, and does not, apply to Palestinians for several reasons. First, as UN delegates involved with drafting the Refugee Convention pointed out: “[T]he obstacle to the repatriation was not dissatisfaction with their homeland, but the fact that a Member of the United Nations was preventing their return.” Second, the Palestinians as an entire group had already suffered persecution by virtue of their massive expulsion from their homeland for one or more of the grounds enumerated in the definition. Thus, they were given special recognition as a group, or category, and not subject to the individualized refugee definition. Third, the delegates dealt with Palestinians as de facto refugees, referring in a general way to those who were defined by the relief agencies at the time (UNRPR and later UNRWA), but not limiting the term “refugee” to those Palestinians who were in need of relief. Although they did not specifically define them as such, the delegates were referring to Palestinian refugees as persons normally residing in Palestine before 15 May 1948, who lost their homes or livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict. For these and other reasons (discussed below, the delegates drafted a separate provision–Article ID–in the Refugee Convention that applies solely to Palestinian refugees.

Refugee Convention Article 1D states:

This Convention shall not apply to persons who are at present receiving from organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection or assistance.

When such protection or assistance has ceased for any reason, without the position of such persons being definitively settled in accordance with the relevant resolutions adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, these persons shall ipso facto be entitled to the benefits of this Convention.

Although Palestinian refugees are not specifically mentioned in this provision, it is evident from both the drafting history and the interrelationship of Article 1D with three other instruments that Palestinians are the only group to which the Article applies. The most important reasons for drawing this conclusion are that, first, the drafting history of the provisions clearly reflects that the only refugee population discussed in relation to Article 1D was the Palestinians. Second, one of the paramount concerns of the drafters of the Refugee Convention was that the wished to determine the precise groups of refugees to which the Convention would apply, so they could decide the extent to which the signatory states could accept the refugee burden. There is no indication that Article 1D was drafted with any different intention–that is, with an open-ended reference to other groups of refugees not contemplated by the United Nations at the time. (The universal application of the Refugee Convention definition is a later development with the entry into force of the Refugee Protocol.) Third, there was only one group of refugees considered to be in need of international protection at the time of drafting Article 1D that was receiving “from other organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection or assistance,” and that was the Palestinians. Fourth, the interrelationship of the mandates of the United Nations agencies relevant to the needs of Palestinian refugees indicates that these are the agencies referred to by the language of Article 1D. These mandates are reflected in the Statute of the UNHCR, the Regulations governing UNRWA, and UN Resolution 194 establishing the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP).

The UNHCR Statute, paragraph 7(c) provides that “the competence of the High Commissioner…shall not extend to a person…who continues to receive from other organs or agencies of the United Nations protection or assistance.” The “other agencies of the United Nations” originally referred to both UNRWA and the UNCCP. The significance of the language in these provisions lies primarily in the distinction between “protection” and “assistance,” which are substantially different concepts in refugee law. UNRWA’s mandate is solely one of providing assistance to refugees’ basic daily needs by way of food, clothing, and shelter. In contrast, UNHCR’s mandate, in tandem with the provisions of the 1951 Refugee Convention, establishes a far more comprehensive scheme of protection for refugees qualifying under the Refugee Convention. This regime guarantees to refugees the rights embodied in international human rights conventions, and mandates the UNHCR to represent refugees, including intervening with states on their behalf, to ensure such protections to them. Aside from the distinction between the mandates of UNRWA and UNHCR, the refugee definition applicable to Palestinians is different from and far narrower under UNRWA Regulations than the Refugee Convention definition. Consistent with its assistance mandate, UNRWA applies a refugee definition that relates solely to persons from Palestine meeting certain criteria who are “in need” of such assistance.” (Susan Akram, “Palestinian Refugee Rights under International Law” in Nasser Aruri’s Palestinian Refugees: The Right of Return. London: Pluto Press, 2001. 166-169)

i realize that the above-quoted passage is rather long, and for some perhaps tedious. but international law, and refugee law more particularly, is complicated. and i think it is important to remember the specificity of the case of palestinian refugees not only because it is world refugee day today, but also because palestinian refugees, unlike the rest of the world’s refugees, do not have an united nations body or agency fighting for their rights as do all other agencies. it was set up like this from the beginning as akram makes clear: unrwa provides assistance, unhcr provides protection and advocacy. this tremendous failing on the part of the united nations means that palestinians have yet another hurdle to face when fighting for their right of return unlike the rest of the world’s refugees. moreover, as a protest in nablus today against unrwa illustrates, unrwa often does not even meet the needs of the refugees it is supposed to be assisting. this is why one can read only one statement for world refugee day on unrwa’s website today in which you will see vapid remarks made by bani ki moon in which he says nothing about the right of return or any political rights of refugees more generally. of course they have organizations like badil, which tirelessly fights for the right of return, but badil does not have the power and weight of the international community behind it, though they do, of course, have the weight of international law behind their work. here is badil’s statement to commemorate world refugee day today:

Statistics released by UN agencies on the occasion of the 2009 World Refugee Day testify to the fact that Palestinian refugees are the largest and longest standing refugee population world wide. They lack access to just solutions and

reparations, including return, because Israel and western governments continue to deny or belittle the scope of the problem and make no effort to respect and implement relevant international law and best practice.According to a forthcoming Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons for the years 2007-2008 produced by Badil, at least 7.6 million Palestinians have been forcibly displaced since 1948 as a consequence of Israel’s systematic policies and practices of colonization, occupation and apartheid. That figure represents 71 percent of the entire worldwide population of 10.6 million Palestinians. Only 28.7 percent of all Palestinians have never been displaced from their homes.

The great majority of the displaced (6.2 million people – 81.5 percent) are Palestinian refugees of 1948 (the Nakba), who were ethnically cleansed in order to make space for the state of Israel and their descendants. This figure includes 4.7 million Palestinian refugees registered with the United Nations (UNRWA) at the end of 2008. The second major group (940,000 – 12.5%) are Palestinian refugees of 1967, who were displaced during the 1967 Arab-Israel war and their descendants.

More attention and concern should be given to the phenomenon of forced displacement of Palestinians because it is ongoing.

Steadily growing populations of internally displaced Palestinians (IDPs) are the result of ongoing forced displacement in Israel (approximately 335,000 IDPs since 1948) and the Occupied Palestinian Territory since 1967 (approximately 120,000 IDPs since 1967). Badil’s Survey identifies a set of distinct, systematic and widespread Israeli policies and practices which induce ongoing forced displacement among the indigenous Palestinian population, including deportation and revocation of residency rights, house demolition, land confiscation, construction and expansion of Jewish-only settlements, closure and segregation, as well

as threats to life and physical safety as a result of military operations and harassment by racist Jewish non-state actors. Israeli

governments implement these policies and practices in order to change the demographic composition of certain areas (“Judaization”) and the entire country for the purpose of colonization.Data about the scope of ongoing forced displacement of Palestinians is illustrative and indicative, because there is no singular institution or agency mandated and resourced to ensure systematic and sustained monitoring and documentation. The total number of persons displaced in 2007 – 2008 is unknown. UN agencies, however, confirm that 100,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes in the occupied Gaza Strip at during Israel’s military operation at the end of the year; that 198 communities in the OPT currently face forced displacement; and that 60,000 Palestinians in occupied East Jerusalem are at risk of having their home demolished by Israel.

The Palestinian refugee question has remained unresolved and forced displacement continues, because Western governments and international organizations have been complicit in Israel’s illegal policy and practice of population transfer and have failed to protect the Palestinian people. Indicators of the severe gaps existing in the protection of Palestinian refugees and IDPs are seen in the recent crises in Iraq – where thousands of Palestinian refugees became stranded on the Jordanian/Syrian and Iraqi borders, Lebanon – where 27,000 Palestinians refugees of the Naher al-Bared camp are still waiting to return to their 2007 destroyed camp, and Gaza – where over 1,400 Palestinians were killed and 100,000 displaced, most of them 1948 refugees).

On this World Refugees Day, Badil calls upon all those concerned with justice, human rights and peace to:

Challenge Israel’s racist notion of the “Jewish state” and immediately halt its practices of displacement, dispossession and colonization; Strengthen the global Campaign for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) in order to ensure that Israel other states become accountable to international law and respect their obligations; Improve the mechanism of international protection so that all Palestinians receive effective protection from, during and after forced displacement, including the right to return as part of durable solutions and reparation; Ensure that the Palestinian refugee question is treated in accordance with international law and UN resolutions in future peace negotiations, including return and reparation.

the situation facing palestinian refugees who lived in nahr el bared refugee camp in lebanon is an excellent example of how unrwa fails the palestinian refugees it is supposed to protect. the crisis of nahr el bared is a microcosm of palestinian refugees in general who have become refugees multiple times over and who are often refugees and idps at the same time. the camp (see map above) continues to be controlled by the lebanese army and the majority of the original 31,000 inhabitants have not been allowed to return–let alone return to their homes in palestine. ray smith’s recent report on the situation of the camp from electronic lebanon is below:

Nahr al-Bared camp consists of an “old” and a “new” camp. The original or “old” refugee camp was established in 1949 on a piece of land 16 kilometers north of the Lebanese city of Tripoli. In 1950, the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) started to provide its services to the camp’s residents. Over the years, population density in Nahr al- Bared rose drastically while refugees who could afford it, left the boundaries of the official camp and settled in its immediate vicinity. This area is now referred to as the “new camp” or the “adjacent area” and belongs to the Lebanese municipalities of Muhammara and Bhannine. While the residents of the new camp benefit from UNRWA’s education, health, relief and social services, the agency has no mandate for the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure and houses in this area.

Since the fighting in the camp ended nearly two years ago, most of the so-called “old camp” has been bulldozed and reconstruction is set to begin within the next month. Along the perimeter of the old camp however the ruins of more than 200 houses are still standing. They’re under the sole control of the Lebanese army, which still prevents residents from returning.

In October 2007, approximately one month after the Lebanese army declared victory, the first wave of refugees was allowed back into parts of the new camp. In the following months, the army gradually withdrew from the new camp and returned the houses and ruins to their former residents. However, the handover wasn’t complete. At least 250 houses in the new camp, adjacent to the old camp, remain sealed off by barbed wire, controlled by the Lebanese army and inaccessible to its residents. These areas are now referred to as the “Prime Areas,” known among the refugees under the Arabized term primaat. They consist of A’-, B’-, C’- and E’-Prime.

Adnan, who declined to give his family name, works in a small shop in the Corniche neighborhood, adjacent to area E’. He has been waiting for the handover of the area by the army. “They tell you, ‘Next week, next month.’ But nothing happens. They say, ‘We first have to remove the bombs and the rubble, then we let people in.’ These are empty words. Nobody is honest. They constantly lie to us,” Adnan complained.

Temporary housing serves as the makeshift office of the Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Commission for Civil Action and Studies (NBRC), a grassroots committee heavily involved in the planning of the reconstruction of the old camp. Abu Ali Mawed, an active member of the NBRC, owns one of the 120 buildings in area E and has been waiting for its handover for 21 months. “The army once more says they’ll open the primaat, but first [the army] will need to [clear] them [of] unexploded ordnance devices and rubble. Where have the parties responsible for this work been in the past two years? Let us be honest: This area could be de-mined and cleared within just under a month!”

Ismael Sheikh Hassan, a volunteer architect and planner with the NBRC, said, “The main reason for the delays is the army. They haven’t taken the decision at command level to allow people to return until last month.”

Since the end of May, things have seemed to finally move forward. On 19 May, an UNRWA contractor started clearing rubble in area B’ and de- mining teams took up their work. UNRWA wrote in its weekly update on 3 June that its contractor had finished clearing rubble in areas B’ and C’. In a meeting among the Lebanese army, Nahr al-Bared’s Popular Committee, Palestinian parties and UNRWA on 2 June, the army announced its intention to allow the return of the residents of these two areas within two or three days. As of 7 June however the promise hadn’t been delivered.

Sheikh Hassan explained that the suspension was mainly due to delays in de-mining procedures and those related to miscommunication among the various structures of the Lebanese army. He expected them to open areas B’ and C’ in a few days. There are 40 houses in B’ and 60 buildings in C’ to be handed over. On 11 June, UNRWA announced that they were told by the Lebanese army that the handover of B’ and C’ would take place mid-month.

The army’s procedures have raised doubts. Abu Ali Mawed, the reconstruction commission member, asked, “How could they allow people last year to return to their burnt, looted and destroyed homes to save some of their belongings, if there were still vast amounts of unexploded ordnance lying around? They should have de-mined the area before letting people in. In the primaat, many houses aren’t completely destroyed, which facilitates de-mining. I suppose that the unexploded ordinance have already been cleared and de-mining is only used as an excuse for further delaying the handover.”

According to UNRWA, the army and the Popular Committee will be responsible for announcing and coordinating the schedules and logistics of families returning to the Prime Areas.

Nidal Abdelal of the Palestinian political faction, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine shook his head: “So far, neither the Popular Committee nor UNRWA understand why the army doesn’t hand the primaat over so people can return. The Lebanese army sets dates [but doesn’t deliver]; this has happened four or fives times. And until today, minor problems in the details constantly prevent them from handing over the primaat.”

Abdelal points out that the persistent delays of the handover dates cause skepticism and worries among the refugees. “They even call UNRWA and the Popular Committee liars,” he says. “They tell people a date, then they postpone it. Then they set another date and again postpone it. In the end, the army controls the primaat and is responsible for their handover. They should eventually hand the areas over to UNRWA and the Popular Committee and let people return.”

Another camp resident, Abu Ali Mawed, compared the situation of displaced residents of Nahr al-Bared to that of southern Lebanese displaced during the summer war of 2006: “Israel dropped about one million cluster bombs in the south, but people could immediately return to their homes [once] the war was over. Why have we for two years not been allowed to return to our houses? … We asked these questions to the government, army representatives and politicians many times, but never got clear answers. They kept giving us lame excuses that were far from convincing.”

Besides the upcoming handover of areas B’ and C’, further questions need to be answered. For example: What will happen to the houses in the primaat once they’re accessible? These houses were assessed and will be stabilized and rehabilitated. If this isn’t possible and their owners agree, they’ll be torn down. An anonymous source with UNRWA believes that only a few homeowners will agree to the total destruction of their homes because other landlords have experienced that the Lebanese government doesn’t sign building permits for Palestinians to build in the new camp.

Currently unscheduled is the handover of areas A’ and E’. Sheikh Hassan of the NBRC says there’s speculation “that those areas will be opening in the upcoming months. However, there are no guarantees on this. E’ will definitely be opened first. A’ will be opened last.” Access to E’ seems to depend on the rubble removal and de-mining process in the adjacent two sectors of the old camp, because they’re still heavily contaminated with unexploded ordnance. According to Nidal Ayyub of UNRWA, the Lebanese army so far has “no plan to open [area] A’.”

However, the Lebanese army did have plans for the construction of an army base in Nahr al-Bared. On 16 January, the Lebanese cabinet decided to establish a naval base in the camp as well. Both plans concern mainly areas A’ and E’ and the coastal strip along the old camp. Just months ago, fierce protest to these plans was voiced by the camp’s residents and the government has reportedly dropped its plans. However, only when the Lebanese army finally makes clear its intentions for the handover of the remaining parts of the camp will residents’ worries be dispelled — or their fears for the future of Nahr al-Bared confirmed.

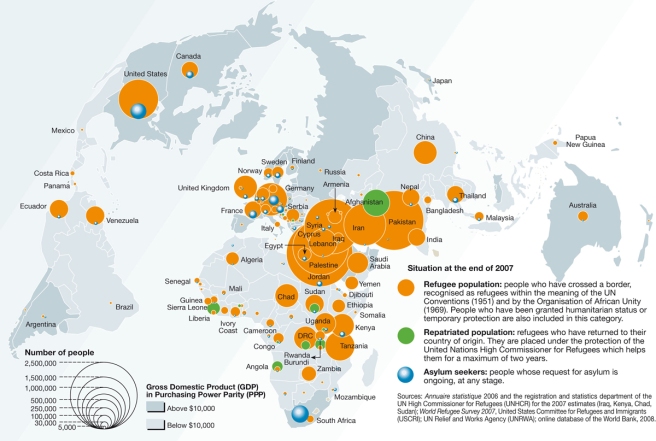

of course palestinian refugees are not the only refugees in the world today, although they are the one refugee population who has been denied their right to return home for the longest period of time. below is a map from the le monde newspaper in 2007 of refugees world wide. while the map is outdated, the general patterns and trends regionally have not changed all that much with the exception of the tremendous recent idp populations in sri lanka and pakistan.

an over view of the global refugee crisis by antónio guterres, the un high commissioner for refugees is as follows, but it should be remembered that last year’s report to which guterres refers to does not include recent statistics about idps in pakistan and tamils in sri lanka:

This overall total reflects global displacement figures compiled at the end of 2008. But the number has already grown substantially since the beginning of this year with more large displacements in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Somalia totaling well over 2.3 million people. And there are more worrisome signs on the horizon.

While some displacement situations are short-lived, others can take years and even decades to resolve. At present, for example, UNHCR counts 29 different groups of 25,000 or more refugees in 22 nations who have been in exile for five years or longer. This means that nearly 6 million refugees are living in limbo, with no solutions in sight. Millions more internally displaced people (IDPs) also are unable to go home in places like Colombia, Iraq, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia.

In addition to prolonged conflict and the increasingly protracted nature of displacement, we are also seeing a decline in the number of refugees and internally displaced people going home. In 2008, about 2 million people were able to repatriate, but that was a sharp drop from the year before. Refugee repatriation (604,000) was down 17 percent in 2008, while IDP returns (1.4 million) dropped by 34 percent. It was the second-lowest repatriation total in 15 years and the decline in part reflects deteriorating security conditions, namely in Afghanistan and Sudan.

In 2008, we also saw a 28 percent increase in the number of asylum seekers making individual claims, to 839,000. South Africa (207,000) was the largest single recipient of individual asylum claims, followed by the United States (49,600), France (35,400) and Sudan (35,100).

The global economic crisis, gaping disparities between North and South, growing xenophobia, climate change, the relentless outbreak of new conflicts and the intractability of old ones all threaten to exacerbate this already massive displacement problem. We and our humanitarian partners are struggling to ensure that these uprooted people and the countries hosting them get the help they need and deserve.

Some 80 percent of the world’s refugees and internally displaced people are in developing nations, underscoring the disproportionate burden carried by those least able to afford it as well as the need for more international support. It also puts into proper perspective alarmist claims by populist politicians and media that some industrialised nations are being “flooded” by asylum seekers. Most people forced to flee their homes because of conflict or persecution remain within their own countries and regions in the developing world.

Major refugee-hosting nations in 2008 included Pakistan (1.8 million); Syria (1.1 million); Iran (980,000); Germany (582,700), Jordan (500,400); Chad (330,500); Tanzania (321,900); and Kenya (320,600). Major countries of origin for refugees included Afghanistan (2.8 million) and Iraq (1.9 million), which together account for 45 percent of all UNHCR refugees. Others were Somalia (561,000); Sudan (419,000); Colombia (374,000), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (368,000). Nearly all of these countries are in the developing world.

Unfortunately, however, we cannot say that generosity and wealth are proportional to each other. As conflicts drag on with no political solutions, the pressure on many of these poor countries is nearing the breaking point. They need more international help now. Without it, UNHCR and other aid agencies will be forced to continue making heartbreaking decisions on which necessities must be denied to uprooted families.

Of the global total of uprooted people in 2008, UNHCR cares for 25 million, including a record 14.4 million internally displaced people — up from 13.7million in 2007 — and 10.5 million refugees. The other 4.7 million refugees are Palestinians under the mandate of the UN Relief and Works Agency.

Although international law distinguishes between refugees, who are protected under the 1951 Refugee Convention, and the internally displaced, who are not, such distinctions are absurd to those who have been forced from their homes and who have lost everything. Uprooted people are equally deserving of help whether they have crossed an international border or not. That is why UNHCR is working with other UN agencies to jointly provide the internally displaced with the help they need, just as we do for refugees.

My agency’s caseload of internally displaced has more than doubled since 2005. Displaced populations include Colombia, some 3 million; Iraq 2.6 million; Sudan’s Darfur region, more than 2 million; Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1.5 million; Somalia 1.3 million. Other increases in displacement in 2008 were in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Georgia, Yemen.

of course most of the above conflicts that create refugee or idp problems can be blamed on covert or overt occupation, wars, and proxy wars initiated or fomented by the united states. but the united states continues to drag its feet with respect to its responsibilities related to refugees, in large part because of either covert operations shielded by proxy fighters or by installing puppet regimes in places like pakistan and afghanistan so that the u.s. can relinquish its responsibilities under international law. two reports on al jazeera today highlight twin poles that many refugees face: return to their homeland or resettle in a third country. most refugees are not able to make such choices, but these reports highlight the difficulties that refugees face in either scenario. the first report is by yvonne ndege who reports on burundi refugees returning home and the challenges they face with respect to their land being occupied by their compatriots because of the government’s take over and re-distribution of the land:

the second report is by nazanine moshiri who reports on difficulties facing afghan refugees resettled in the united kingdom:

in honor of these and all refugees who have the right to determine their own fate–whether reclaiming their rights to return to their homeland or resettling in a third country, here is the amazing suheir hammad’s “on refugees” accompanied by dj k-salaam:

here are hammad’s lyrics:

Of Refuge and Language”

I do not wish

To place words in living mouths

Or bury the dead dishonorablyI am not deaf to cries escaping shelters

That citizens are not refugees

Refugees are not AmericansI will not use language

One way or another

To accommodate my comfortI will not look away

All I know is this

No peoples ever choose to claim status of dispossessed

No peoples want pity above compassion

No enslaved peoples ever called themselves slavesWhat do we pledge allegiance to?

A government that leaves its old

To die of thirst surrounded by water

Is a foreign governmentPeople who are streaming

Illiterate into paperwork

Have long ago been abandonedI think of coded language

And all that words carry on their backsI think of how it is always the poor

Who are tagged and boxed with labels

Not of their own choosingI think of my grandparents

And how some called them refugees

Others called them non-existent

They called themselves landless

Which means homelessBefore the hurricane

No tents were prepared for the fleeing

Because Americans do not live in tents

Tents are for Haiti for Bosnia for RwandaRefugees are the rest of the world

Those left to defend their human decency

Against conditions the rich keep their animals from

Those who have too many children

Those who always have open hands and empty bellies

Those whose numbers are massive

Those who seek refuge

From nature’s currents and man’s resourcesThose who are forgotten in the mean times

Those who remember

Ahmad from Guinea makes my falafel sandwich and says

So this is your countryYes Amadou this my country

And these my peopleEvacuated as if criminal

Rescued by neighbors

Shot by soldiersAdamant they belong

The rest of the world can now see

What I have seenDo not look away

The rest of the world lives here too

In America

and for those who feel inspired to take action today who are in the united states i encourage you to take action against trader joe’s as a part of the global boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement that is fighting for the right of palestinian refugees to return to their land:

On Saturday, June 20, activists will gather at Trader Joe’s in different cities to demand that the company stop carrying Israeli goods such as Israeli Couscous, Dorot frozen herbs, as well as Pastures of Eden Feta cheese. A letter was sent to Trader Joe’s on June 6, 2009 but no response has been received yet. More than 200 individuals and organizations signed the letter. Note that we are not calling for a boycott of Trader Joe’s.

Join us in this nationwide action! Plan one in your local community!